Not Completely Unknown (E02)

The second podcast in our Not Completely Unknown series is the world premiere of the podcast version of Dylan Revisited. It tells the story of Bob Dylan’s debut on Columbia Records, an album recorded in late ‘61 and released in March 1962.

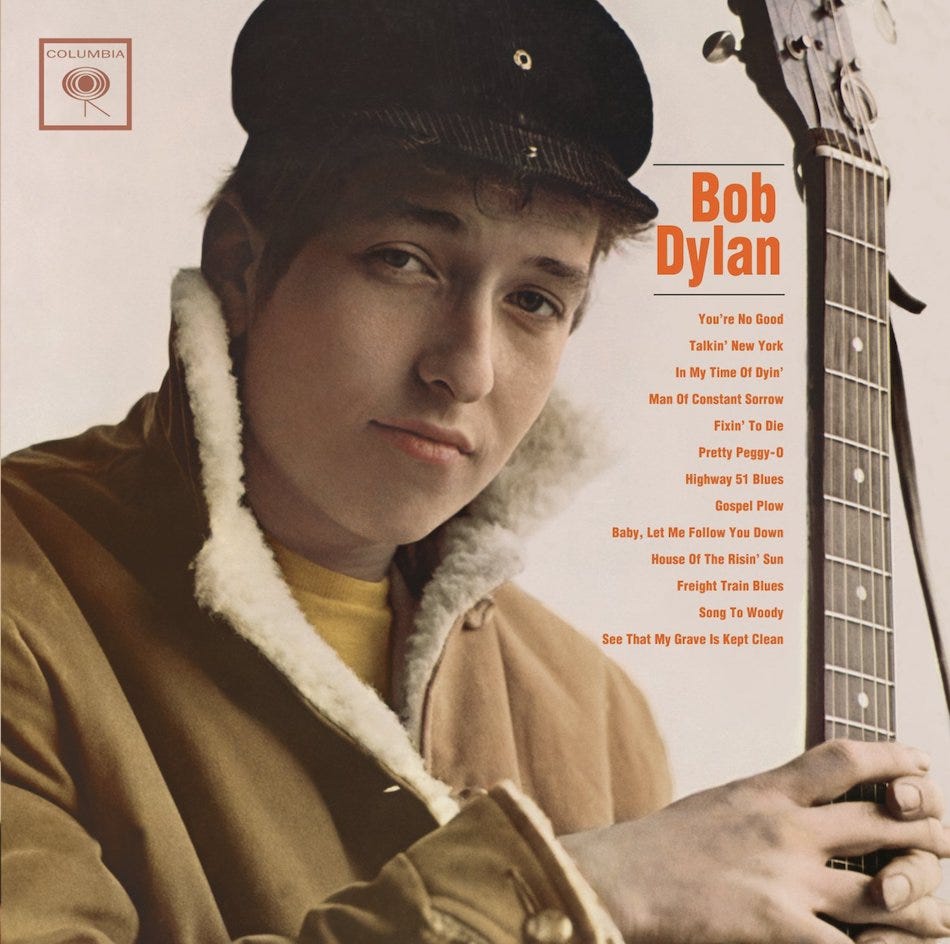

Who is this guy? Seriously, do you recognize that baby-fattened, cap-wearing troubadour staring at you with those soft eyes and the hint of a smile?

Zoom out and the answer is right there, in bold red letters separating that unfamiliar head from the neck of his guitar. It’s Bob Dylan. This is his self-titled debut album. His introduction to the world. Yet, it’s a highly un-Bob Dylan record.

The world’s most renowned songwriter only composed two of his debut record’s 13 songs. Instead of that familiar nasal drone, he often sings in a grating, grizzled voice. But the most un-Dylan thing about this record is that few people were interested in it.

Bob Dylan’s debut album only sold 2500 copies during its initial 1962 release. While some were put off by unenthusiastic reviews, most were just unaware of its existence. No Dylan album after this would ever be met with such indifference.

Even Dylan’s deliberate acts of sabotage like Self Portrait, the much-derided Christian era and his late-career crooning were greeted by loud critical pearl-clutching best summed up by the opening line of Greil Marcus’ infamous Self Portrait review: “what is this shit?”

Revisiting Bob Dylan’s debut album more than 60 years later, Marcus’ sweary demand would be a harsh starting point. Instead, let's go back to my opening query, “who is this guy?”.

It’s a question that most listeners of the album back in 1962 would have needed answering. Dylan wasn’t well known outside of the small Greenwich Village folk circuit. Even his friends and family back home in Minnesota might have struggled to reconcile the name on the record cover with the face of their old pal Robert Zimmerman.

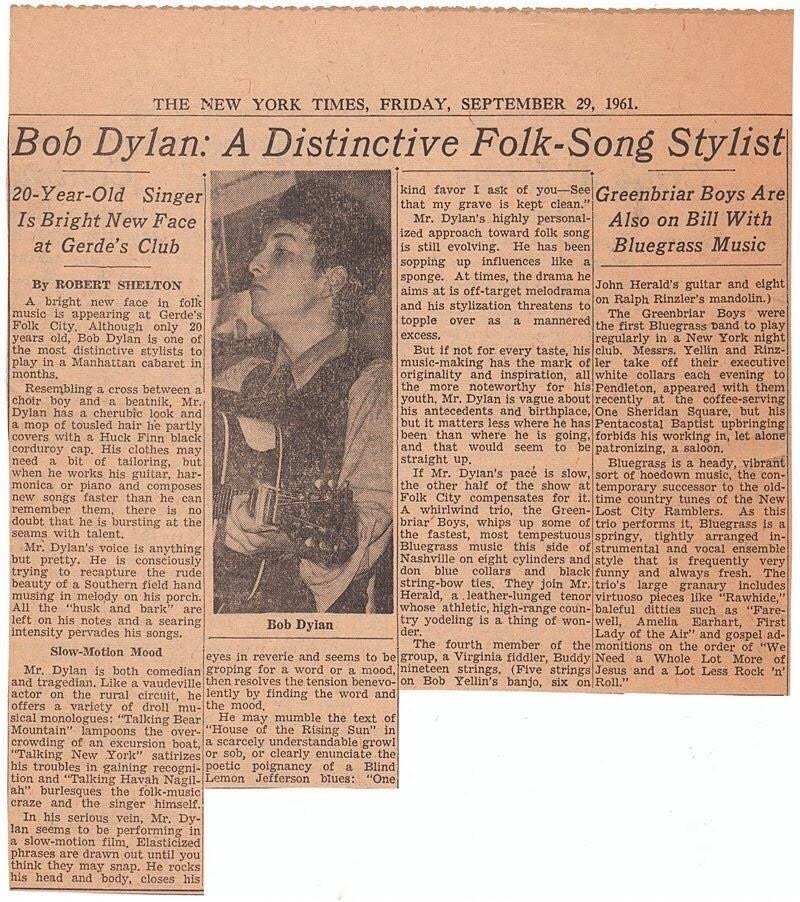

The only significant suggestion that Bob Dylan was worth your attention was a live review from 1961 by The New York Times’ folk music correspondent, Robert Shelton. Calling him a “bright new face in folk music” and a “distinctive stylist”, Shelton made the supporting performer at Gerdes Folk City on a mid-September evening the headline act of his review.

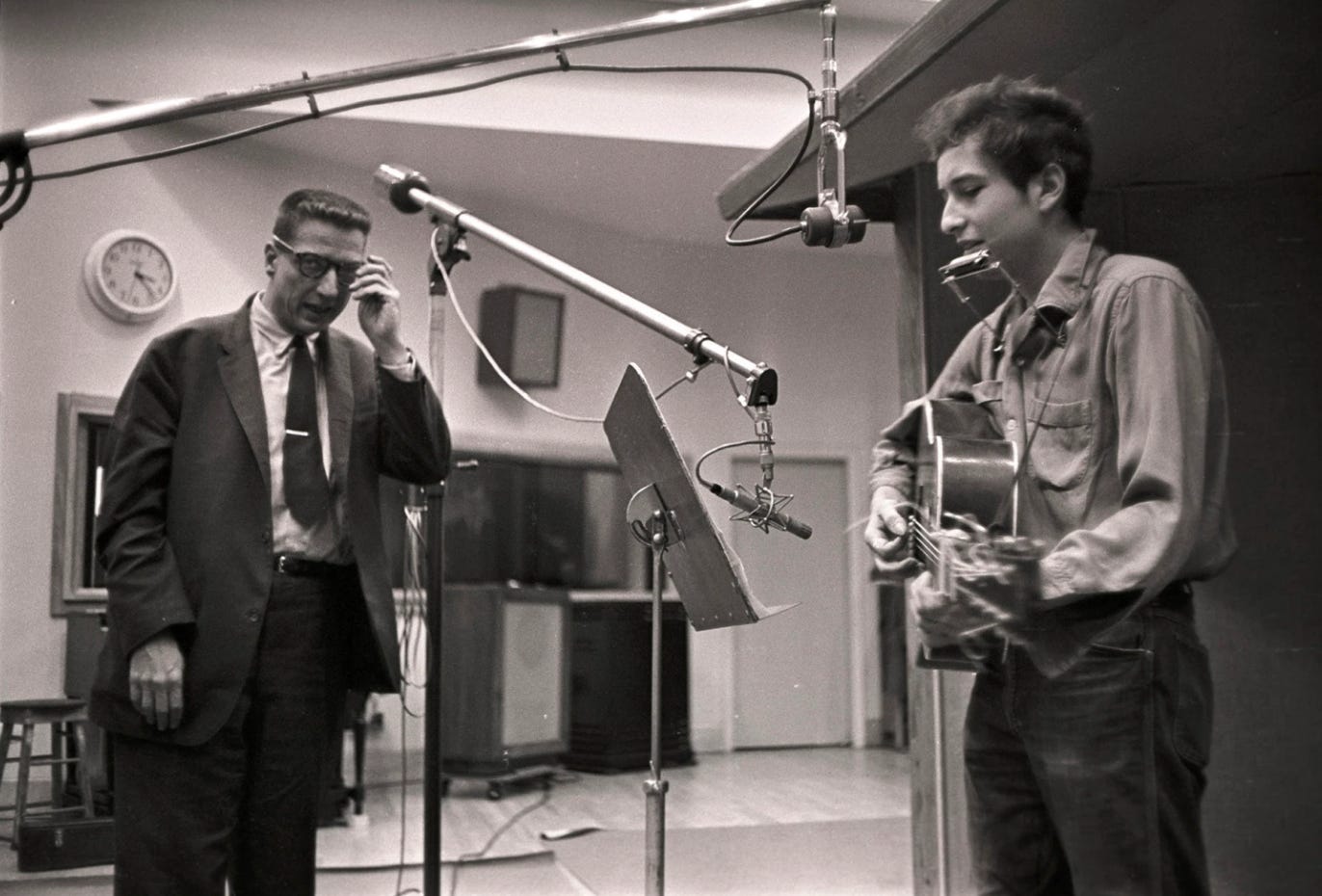

The legend goes that the glowing NYT write-up caught the eye of Columbia Records executive John Hammond, who had given Billie Holiday and Count Basie their first big breaks and would go on to sign Leonard Cohen and Bruce Springsteen.

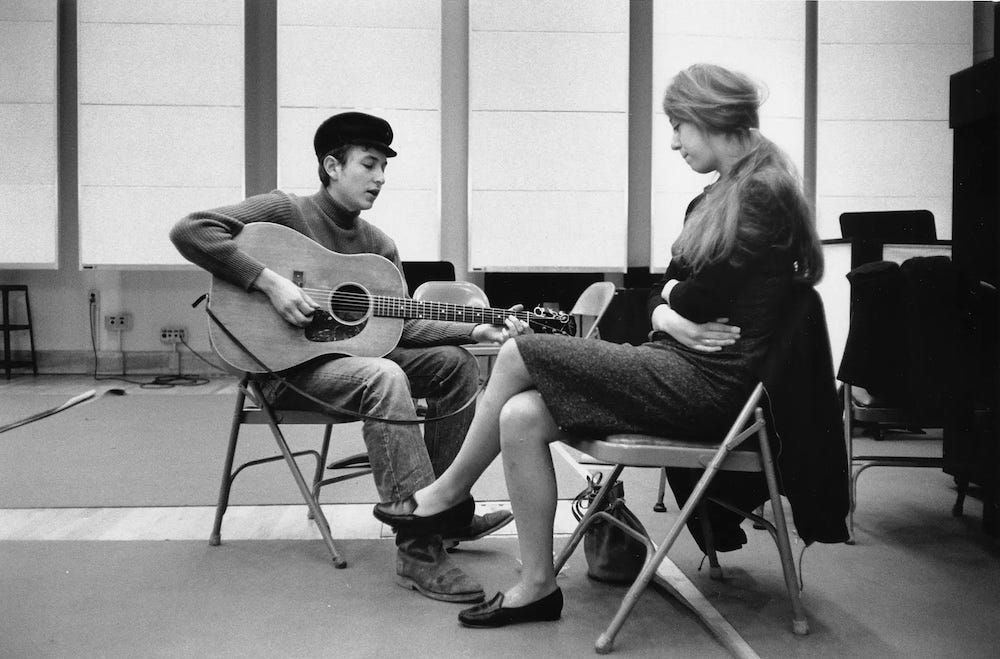

However, Hammond had already met Dylan two weeks earlier when the singer was playing harmonica at a rehearsal session for Columbia artist Carolyn Hester. Hammond liked him straight away and was ready to offer Dylan a contract on the same day that Shelton’s review was printed.

The critic had also wondered who Dylan was, mentioning in his review that the singer was “vague about his antecedents and birthplace”. Around this time, Dylan had a habit of enhancing, exaggerating and even outright inventing the details of his past (including his name).

Perhaps this uncertainty contributed to the crisis of confidence that seemed to affect the 21-year-old singer once he’d finally secured a record deal after months of gigging for tips in Greenwich Village’s basket-houses and cafes.

Rather than simply refine and record the material he had been playing live, Dylan spent two manic weeks seeking out new songs. This largely involved riffling through the record collections of friends and acquaintances, often pilfering the ones that caught his ear.

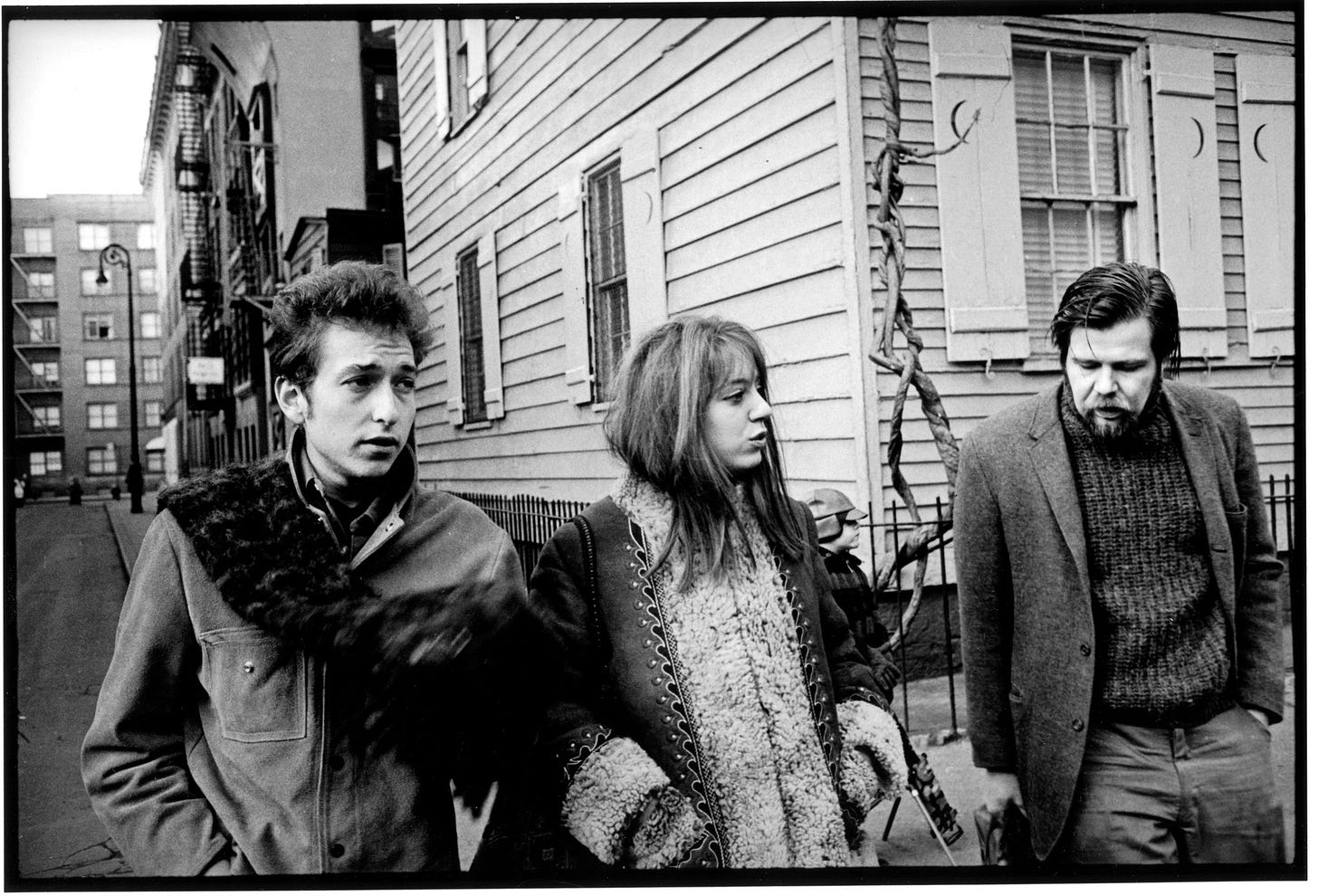

He was similarly light-fingered when it came to his fellow musicians, especially in the case of his sometime mentor Dave Van Ronk. A major figure in the Village folk scene - known as the Mayor of MacDougal Street - Van Ronk often let Dylan stay in his apartment and taught him songs.

One of those was his own arrangement of the traditional blues tune, House of the Rising Sun. When Dylan asked Van Ronk if he could use it for his debut, Van Ronk replied that he had plans to record it himself. But Dylan wasn’t asking for permission, he was begging for forgiveness, having already cut the track for Columbia.

At least House of the Rising Sun was a song Dylan knew well. He recorded the gospel blues number In My Time of Dyin’ having never played it before entering Columbia’s Studio A. And once was enough for the singer who refused a second take, as he did with at least four other tracks recorded for the album over three days.

Dylan was ok with an imperfect recording if the overall feel of a song was right. But this approach infuriated producer Hammond, who was also exasperated by the singer’s lack of studio experience. He complained that Dylan was always either wandering away from the mic or popping his Ps and, worst of all, never learned from his mistakes.

Then there’s the over-the-top growl Dylan adopts on In My Time of Dyin’, Highway 51 Blues, the traditional spiritual Gospel Plow and Fixin’ to Die - a song by Delta bluesman Bukka White.

In his live review, Shelton had praised Dylan for how “all the husk and bark are left on his notes”. If the singer increased the crust on his recording vocals to sound more like the bluesmen whose songs he was singing, the results are somewhat inauthentic.

It's telling that he never returned to that vocal style or these songs after the album’s release, bar a couple of performances in 1962 and ’63 of Highway 51 Blues, which was originally written by blues pianist Curtis Jones.

His voice on Man of Constant Sorrow is more natural and the song is better for it. It’s also notable for his changing “your friends say I’m a stranger” to “your mother says…”. This is potentially a first reference to then girlfriend Suze Rotolo, who was at the studio during recording. According to Hammond’s liner notes on the album, Dylan used her lipstick holder to play slide guitar on In My Time of Dyin’.

Rotolo’s mother and her daughter’s boyfriend did not get on well, which may account for little lyric change on Man of Constant Sorrow. She would once more be mentioned on a Dylan song two years later – that bitter document of his and Suze’s breakup, Ballad in Plain D.

Bob Dylan’s debut album opens with the slight (and annoying) You’re No Good, a cover of a song by the Georgia-born blues musician Jesse Fuller, who played guitar, harmonica, kazoo, percussion and bass all at the same time. Apparently, Dylan picked up the idea of using a harmonica brace from this one-man band.

Next comes the first Dylan original. Talkin’ New York’s rambling jokes mostly fall flat on record, especially when compared to the live versions from around this time. I find that the talkin’ blues format often loses something when you can’t hear an audience’s reactions.

After the growling trifecta of death and sorrow that begins with In My Time of Dyin’, Pretty Peggy-O brings us back to the upbeat, rollicking style of the opening two songs. This American traditional based on a Scottish ballad is one that Dylan returned to a lot for his live shows during the 1990s.

Overall, the first half of Bob Dylan’s debut album is surprisingly average. It’s hard to imagine listeners from 1962 being blown away so far. But nine songs in, we finally hear something great.

Baby, Let Me Follow You Down starts with a breezy acknowledgment of the song’s original arranger Eric Von Schmidt and a playful jab at folk purists, who wouldn’t have seen the “green pastures of Harvard University” as fertile soil for authentic folk music.

In this relaxed but engaged performance, Dylan’s voice bears little affectation and both his guitar playing and harmonica interludes are lovely. In a few years, he’ll mischievously turn this genial folk song into a riotously electric rock number for another, much more combative dig at the folkerati.

Song to Woody is the album’s second original and one of the first songs Bob Dylan wrote. Prior to this he hadn't considered himself a songwriter but no-one else could express what he needed to say: a literal and symbolic farewell to his hero Woody Guthrie.

Dylan spent years learning Guthrie’s songs, aped his look and regularly visited the folk legend in the New Jersey hospital where he lived out his final years while suffering from Huntingdon’s disease.

Song to Woody is based on Guthrie’s 1913 Massacre, while also referencing lyrics from some of his other songs, including Hard Travelin’ and Pastures of Plenty (“We come with the dust and we go with the wind.”)

An early Dylan classic, Song to Woody is a fine tribute to Woody Guthrie but also the songwriter’s way of moving on. After this, his regular visits to Guthrie in hospital ceased and different Dylan personalities began to supersede his impression of Woody.

Before that important moment is the disposable Freight Train Blues, the last song recorded for the album. Dylan likely heard this via country singer Roy Acuff and he sounds like he’s having fun delivering the song at breakneck speed, pausing only to sustain a yodel for a remarkably long time.

The album closes with Blind Lemon Jefferson’s See That My Grave Is Kept Clean, a song that Shelton called out in his Gerdes review. This is the best of the record’s bluesy growly stuff and features some excellent guitar playing from Dylan.

Revisiting Bob Dylan’s 1962 debut album 60 years later is largely an underwhelming experience. Would the songs he also recorded at the time but did not include have improved it?

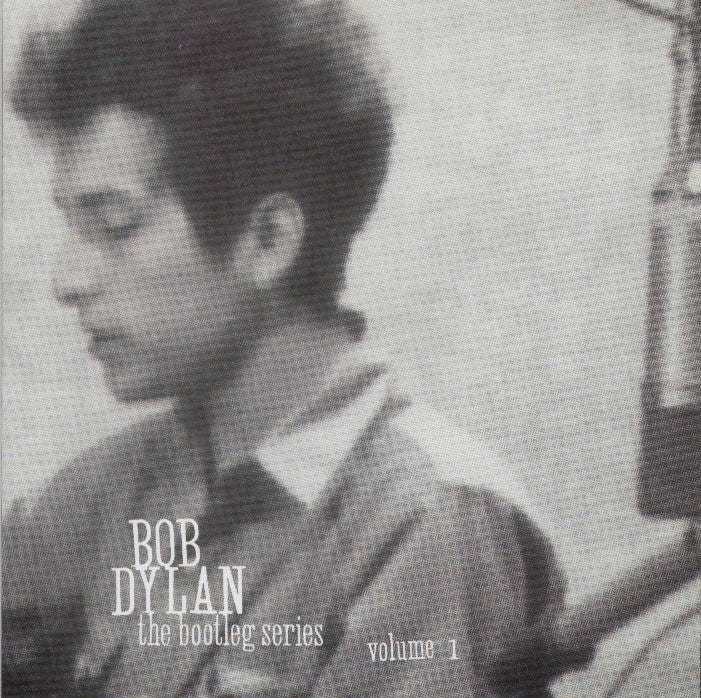

The outtakes from the three short studio sessions, which officially came to light on the first volume of The Bootleg Series, include a great take on the Scottish standard, House Carpenter. Dylan introduces it as the “story of a ghost coming out of the sea” and proceeds to tell his tale with great intensity and rhythm.

Dylan also delivers an achingly sad version of He Was a Friend of Mine. It’s another Von Schmidt arrangement so maybe he didn’t want two of these on his record. Dave Van Ronk would later record the song and miscredit Dylan (the arrangement thief) as the writer.

Man on the Street is another Dylan original, though like Song to Woody, it leans heavily on traditional melodies and lyrics. The lyrics are an early herald of the slew of socially minded, topical songs that will soon come pouring out of him.

Each of these songs seems much more in the mould of the Bob Dylan to come, but he rejected them in favor of gritty, death obsessed blues numbers. This was also around the time he told people that he rode the rails down South – he was committing to the blues mythos in story and song.

Dylan would later say that he didn’t want to give away too much of himself on the record. Perhaps his studio stubbornness and raw performances of minor standards suggest a wariness about his major label polishing him into something more palatable.

His obstinacy worked, as Bob Dylan the album was not a commercial success. Most critics weren't impressed either, except the Billboard reviewer who said “Dylan, when he finds his own style, could win a big following.”

In Martin Scorsese’s brilliant documentary, No Direction Home, Dylan recalls that after hearing the finished record, “I was highly disturbed. I just wanted to cross this record out and make another record immediately. I thought I’d recorded the wrong songs and I’d already written new ones.”

A month after the release of his debut album in March 1962, Dylan was back in the studio to work on The Freewheelin’, where he would find his own voice and confirm Shelton’s view that he had “the mark of originality”.

The album that kickstarted a six decade long recording career, the one that bears his name, was not really Bob Dylan.

DylanRevisited is a Bluesky account (@dylanrevisited.bsky.social) where writer and longtime Dylan fan Colm Larkin revisits Bob Dylan's back catalogue one album/bootleg/live record at a time.

Not Completely Unknown is our series for new and emerging Bob Dylan fans.

Click here to see more podcasts and posts from this series.