Dylan Revisited: Folksinger's Choice (1962)

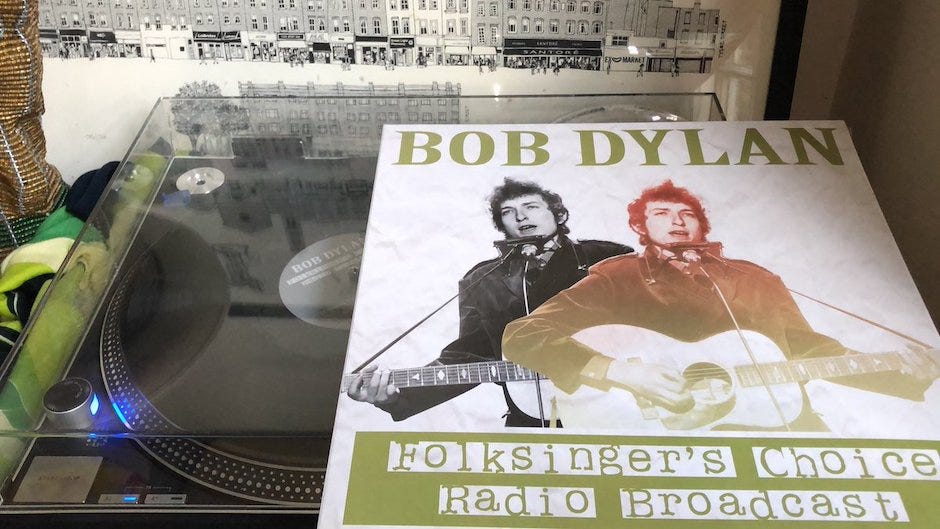

Bob Dylan's first radio interview features sparkling conversation with host Cynthia Gooding and superb performances of original and traditional material.

This is a series by DylanRevisited based on former Twitter threads, now available here in an easier to read and longer lasting format.

“That was Bob Dylan. Just one man doing all that.”

This was how Cynthia Gooding introduced the March 11th 1962 episode of Folksinger’s Choice, her regular show on WBAI 99.5FM New York.

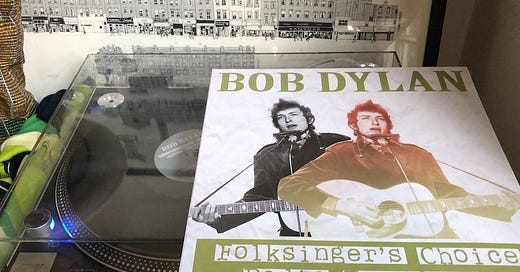

Photo by Vainglorious Vinyl

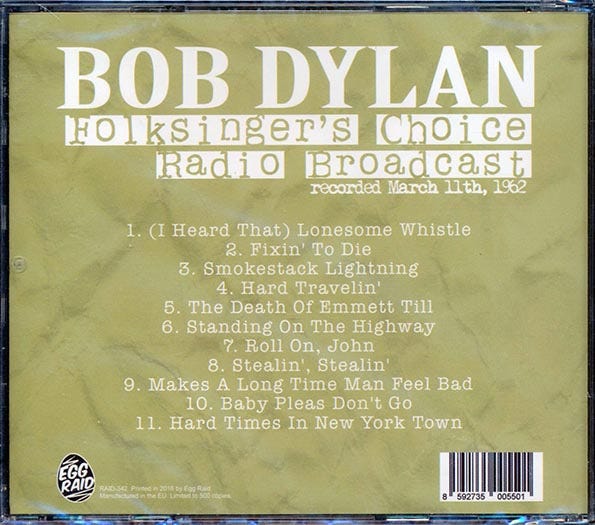

Dylan had just played a fine version of the Hank Williams classic, (I Heard That) Lonesome Whistle. In a lovely, relaxed performance, he exaggerates his accent and plays with the "oh" sounds, just like Williams did.

Though it’s one of his first radio interviews, Dylan is more excited about playing music than talking. It’s likely he hadn’t performed live much since a November show at Carnegie Chapter Hall, as he spent the end of 1961 preparing for and recording his debut album.

“You wanna hear a blues song?” he asks Gooding before launching into a cut from that eponymous record (“that’s a novel title” she jokes). Though the radio show was recorded in January 1962 - just two months after his sessions at Columbia’s Studio A - Dylan appears to have already moved on from his upcoming release.

Fixin’ to Die is the only song of the 11 he plays for Gooding that features on his debut. It’s nice to hear it without the album version’s affected growl. His guitar playing is also more expansive on this engaging take.

Gooding is a wonderful audience. After finishing Howlin’ Wolf’s Smokestack Lightning, Dylan coyly asks “you like that?” In a misty, musical voice, that’s both brusque and convivial, she tells him, “I sure do…you’re very brave to try and sing that”.

As the show title suggests, Gooding is a singer herself and had released a few albums on Elektra Records. A one-time resident of Mexico City, she recorded La Bamba before Ritchie Valens had a hit with it and before Dylan appropriated its chord patterns for Like a Rolling Stone.

Cynthia Gooding also collaborated with Theodore Bikel, one of the co-founders of the Newport Folk Festival. In 1965, Bikel had to talk down an exasperated Pete Seeger as they watched The Paul Butterfield Blues Band play an electric set at the festival.

Bikel wisely reminded Seeger that “these rebels, they’re us…20 years ago”. Those new radicals turned out to be Dylan's electric heralds.

After hearing the legendary folk music collector Alan Lomax disparage The Paul Butterfield Blues Band’s sound, Dylan recruited a few of its members to play his own raucously loud rock’n’roll on the following day. This short set further scandalized the folk set, including Seeger who, according to legend, wanted to cut the power with an axe.

Dylan had become the idol of the Newport crews after he wrote a slew of topical songs in the three years between his Folksinger’s Choice and Newport 1965 appearances. Bikel had encouraged the political side of Dylan, convincing manager Al Grossman that his charge should attend a voter registration rally in Greenwood, Mississippi.

“Tell him it’s time to go down and experience the south”, said Bikel. Dylan took on the journey with Pete Seeger in July 1963, where he was recorded performing a stirring version of Only a Pawn in their Game.

But long before that trip, Dylan had written a Mississippi-set song, which he performs for Cynthia Gooding on Folksinger's Choice. After a stunning version of The Death of Emmett Till, Gooding is effusive in her praise.

“It’s one of the greatest contemporary ballads I’ve ever heard – it’s tremendous.” She’s almost breathless when she says, “it makes me very proud”. When Dylan next asks “You wanna hear another one?”, Gooding replies, “I wanna hear tons”.

As much as this episode of Folksinger’s Choice is a wonderful document of Dylan’s early repertoire of songs, much of its pleasure lies in the chemistry between Gooding and her guest.

The pair have an easy patter though Gooding still slyly probes with some of her questions. When she recalls seeing him in Minnesota years earlier playing rock’n’roll, he’s quick to clarify that he was playing Muddy Waters and Johnny Cash songs.

If Dylan doesn’t yet want to be seen as a rocker, he’s equally keen not to be pegged too closely to the folk scene, noting that he also plays blues and country songs. Speaking about his own compositions, he states: “I don’t call them folk songs...I just call them contemporary”.

The affable folksinger Gooding seems happy to hear whatever kinds of music Bob Dylan wants to play. She is also fascinated by his harmonica holder, detailing how he puts on what she bemusedly calls “a necklace”.

“Is there a more dignified name for that?” she asks. He replies, “Uh, harmonica holder”.

Dylan was preparing to play the Woody Guthrie song Hard Travelin’, to which he adds a harmonica intro. It’s a cracking performance that builds in tempo and force and wouldn’t sound out of place on The Freewheelin’, the follow-up album that he’ll work on throughout 1962.

He straps on the harmonica again for a lively version of the Memphis Jug Band song, Stealin’. Dylan has a lot of fun with this and you can hear Gooding laugh along throughout.

After Stealin’, Gooding asks, “You haven’t been playing the harmonica a long time, have you?” While this sounds like she’s in the Larry Adler camp when it comes to Bob’s harp skills, he doesn’t appear to take offense.

In fact, Dylan is so relaxed in Gooding’s company that he starts making up stuff. After Standing on the Highway – a self-penned song he’d later record as a demo for Leeds – she compares the lines about the ace of diamonds and spades to card reading.

Dylan uses the cue to claim that he traveled with a carnival for six years, working as a clean-up boy and on the Ferris wheel. Naturally that meant missing school but according to Dylan, “it all came out even though”.

Later he returns to the theme telling Gooding about a woman he knew who performed as a freak and the song he wrote about her (but conveniently can’t remember). It’s remarkable stuff.

Though it sounds like he’s improvising, Dylan had previously spun versions of the carnival story to New York Times critic Robert Shelton when they spoke backstage at Gerde's Folk City and during a show to promote his 1961 Carnegie Chapter Hall show.

We now know it’s all untrue and that Dylan had a very regular middle class upbringing and schooling. But he understood that the largely middle-class folk audience enjoyed the supposed authenticity of performers who came from less comfortable backgrounds than their own.

Back then you could get away with mythologising your past, especially with an interviewer like Gooding, who first met Dylan as a university student in Minneapolis, but is prepared to indulge his far-fetched carnie tales. These days, any such claims would be disproved in few clicks and held up as a sign of inauthenticity.

Instead of playing his carnival freak song, Dylan opts for Makes a Long Time Man Feel Bad, a work song collected by Alan Lomax around 1947 and later recorded by Ian and Sylvia. This Canadian folk duo got a record deal with help from Al Grossman, soon to become Dylan’s manager.

They’d go on to record Dylan’s Tomorrow is a Long Time and later some of his Basement Tapes songs. They were also at Newport in 1965 and Sylvia Tyson recalled Pete Seeger crying when Dylan plugged in.

There’s a foreshadowing of these future events when Dylan plays Baby Please Don’t Go - the delta blues traditional that will be a rock’n’roll hit for Van Morrison and Them in 1964. Here Dylan uses it to showcase that he’s more than just a folk singer.

Earlier in the set, he plays a gorgeous slow bluegrass song called Roll on John, which he learned from Ralph Rinzler of The Greenbriar Boys. This was the group that headlined the September 1961 show at Gerde’s that led to Shelton’s rave review of Dylan’s support act.

Gooding is enthralled by Roll on John, saying: “that’s a lonesome accompaniment too – oh my”. 50 years later, Dylan will write and record a different song with that title for his 2012 album Tempest, as a tribute to John Lennon.

I’d love to know what Cynthia Gooding thought about Bob Dylan’s career after their magical hour together in 1962. She liked Emmett Till because it lacked "those poetic contortions that mess up so many contemporary ballads". What would she have made of a song like Gates of Eden?

But in March 1962, none of that storied future was obviously in the cards for a man who plainly states, “I’m never gonna become rich and famous”. And he ends his Folksinger’s Choice set with that jaunty tale of struggle, Hard Times in New York.

“That’s a very nice song Bob Dylan”, exclaims Cynthia Gooding, bringing to an end a fine set from the young performer. You can listen to the entire show here:

Many of Bob Dylan’s contemporaries recall the young man's ability to soak up songs. On Folksinger’s Choice, we are fortunate to hear an early sample of that musical range. It will inform and influence the next 60 years of Bob Dylan’s art.

An interesting post-script to Dylan’s radio appearance is a home-taped recording of him playing songs at Gooding’s home. This intimate session took place on February 16th 1962 - between the radio show recording in January and its March broadcast.